NEW YORK -It’s all about the Benjamins baby!!

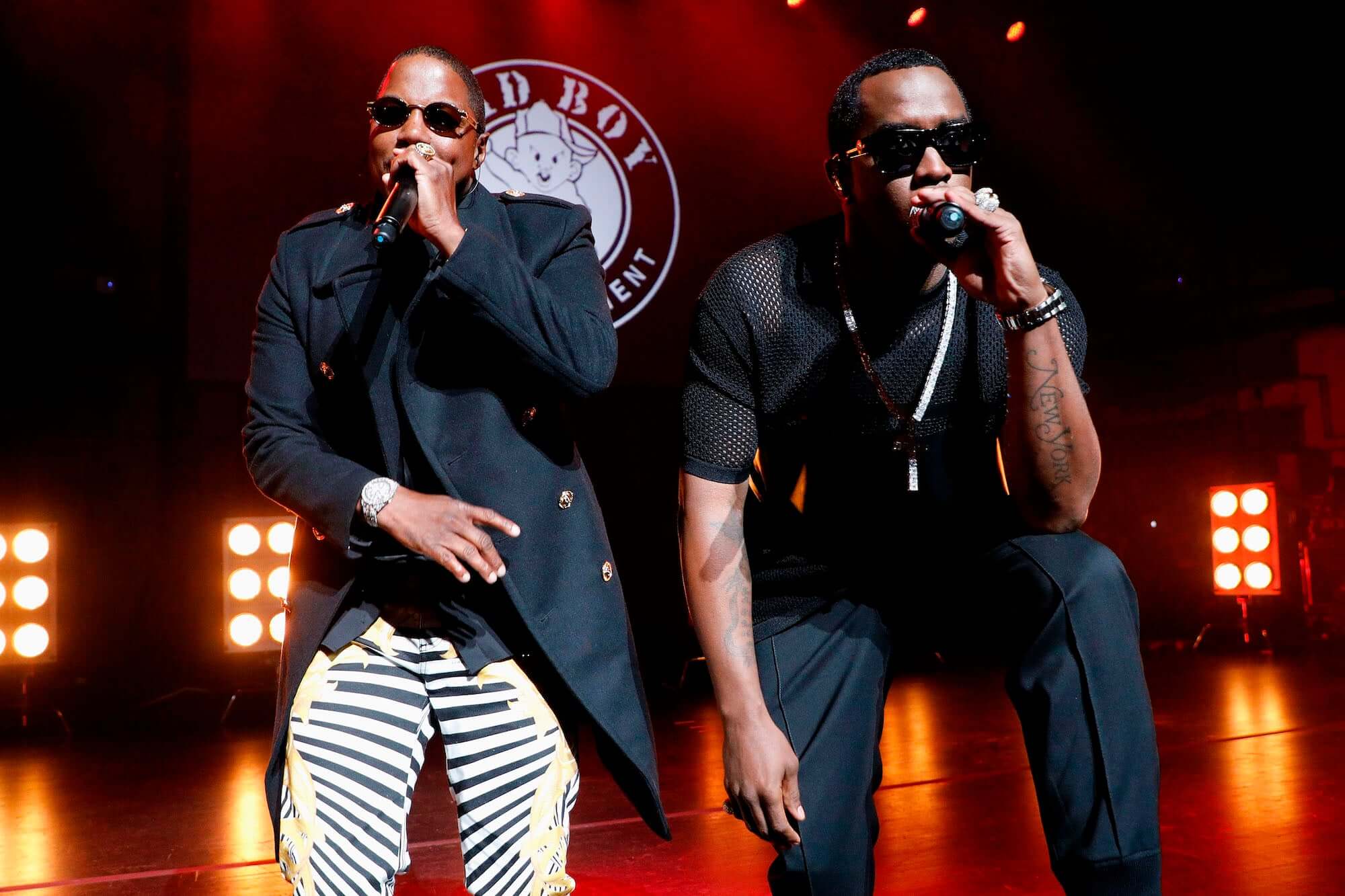

The famous lyric made known by Sean “Diddy” Combs and his Bad Boy Records’ artists in its heyday of the 90s, came full circle this week when Mason Betha a.k.a “Mase”, a multi-platinum selling artist, once signed to the label, went public Friday night and called out Diddy.

“I heard your #Grammy speech about how u are now for the artist and about how the artist must take back control,” Mase wrote on Instagram. “So, I will be the first to take that initiative.”

The rapper known for hits while signed to Diddy like “Mo’ Money, Mo’ Problems” and “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down”challenged Combs publicly, “if you want to “see change you can make a change today by starting with yourself.”

“Your past business practices (Diddy), knowingly has continued purposely starved (sic) your artist and been extremely unfair to the very same artist that helped u obtain that Icon Award on the iconic Bad boy label,” Mase angrily highlighted on his wall. “For example, u still got my publishing from 24 years ago in which u gave me $20k.”

Mase is not alone in his claims that the music industry mogul allows his artists to struggle, while he has built a reported $700 million dollar, multi-faceted brand led by Ciroc liquor and the Sean John clothing line.

Mase was one of a list of artists on the recent Bad Boy Label 20 year tour that sold out throughout the country. And, most thought he and Diddy were on the same business page until now.

But, singing before millions on stage is one thing; we are now talking about copyrights to dozens of songs that make millions of dollars quietly, each day when millions of people stream, purchase remakes and networks and film companies license these songs repeatedly.

In fact, the Diddy owned publishing catalogue alone is probably easily worth well over $200 million dollars, according to some experts and allegedly includes songs by Faith Evans, 112, Biggie, Total, Craig Mack, Danity Kane, Black Rob, the Lox and Mase, among others, who were signed to Bad Boy.

Over 10 years ago, the late Bad Boy exec Francesca Spero, a right-hand soldier to Diddy at his peak, once said the catalogue had nearly 1,000 songs under publishing contracts with the various artists and songwriters signed to the label and its publishing division, then called Justin Combs Publishing, the name of Diddy’s oldest son and the publishing tag you see on many Bad Boy Records liner notes after a given hit song.

Mase claimed he offered Diddy 2 million and “Your (Diddy) response was if I can match what the EUROPEAN GUY OFFER him that would be the only way I can get it back. Or else I can wait until I’m 50 years old and it will revert back to me from when I was 19 years old.” Mase emphasizing with capital letters the other offer came from a non-African-American.

He also ridiculed Diddy even deeper, stating, “You bought it for about 20k & I offered you 2m in cash. This is not black excellence at all”.

The outrage from Mase comes years after Diddy has been constantly accused of not taking care his core crew of artists, producers and songwriters.

The Lox called him out on NY’s Hot 97 radio station with DJ Angie Martinez over a decade ago for the same issues, claiming he made millions off their double platinum selling “Money Power and Respect” album. Diddy called in and challenged the members to “come by the office” so we can handle this as businessmen.

Mase’s public outcry came on the heels of Diddy accepting an award last weekend at music legend Clive Davis’ annual VIP Grammy dinner party, where the Bad Boy founder challenged the Grammys and music industry to do more for artists and honor hip-hop correctly.

“Truth be told, hip-hop has never been respected by the Grammys,” Diddy said to a loud round of applause and support from the music industry. “Black music has never been respected by the Grammys to the point that it should be.” (For years, Jay-Z has been overlooked and countless white artists have beaten out black artists for top rap awards).

Diddy then gave the industry 365 days to “fix it” and do the right thing by Black artists.

Upon hearing this statement, Meek Mill posted about “slave” contracts and Mase immediately called out Diddy as a top executive and mogul enslaving his own people.

“If it’s about us owning, it can’t be about us owning each other. No More Hiding Behind “Love,” Mase wrote, taking a shot at Diddy’s new moniker Brother Love.

In all caps, Mase, who briefly left the industry to pastor a church in Atlanta emphasized in all capital letters about Diddy, “U CHANGED? GIVE THE ARTIST BACK THEIR $$$. So they can take care of their families.”

Diddy has yet to comment, nor his Bad Boy record label.

The explosive statements by Mase rippled throughout social media with everyone asking, “well what is his catalogue worth, that Diddy refuses to take $2 Million on a $20K investment?”

Only Diddy knows that answer, but be clear, a contract is a contract and Diddy is not required by law to terminate the publishing contract.

However, many artists and Blacks feel like given the history of Black artists being abused by the music industry, it would only seem right for Diddy to make sure he is not maintaining the same abuse and rip-off system in horrible one-sided contracts that Mase eludes to in his posts.

And, Mase is correct on the concept in copyright law known as reversion; when during a certain window, a songwriter can notify the copyright office that he or she is reclaiming the assignment of rights they gave to a publishing company like Diddy’s.

As a lawyer, I normally wait until the 35-year window opens and file with the copyright office to reclaim ownership of the songs and revert back the rights, given away by a young artist-songwriter at a loss of millions. This is why it is known as a reversion situation.

I have done this and it would be a way Mase could reclaim the domestic rights in his copyrights (or songs), but that is still a distant time away, given he signed his contract in the late 1990s. And, it is very complicated and few entertainment lawyers really know how to do it properly.

Thus, Mase doesn’t’ want to wait, he wants his money now.

The Mase Catalogue Could Be Worth $25 Million!

When this was posted on Instagram by the Harlem rapper, my phone began blowing up immediately as most recalled I wrote a chapter in my book “This Business of Urban Music” (Random House) called “The Lox Vs. Puffy” and waxed extensively on how much publishing money was possibly at stake for Jadakiss and his “Money, Power and Respect” album group members.

Whether Mase, Jadakiss or Prince, this debate has been exhausted on radio, in pool halls, barber shops and on the street regarding the millions of dollars in income a songwriter gives up when he or she signs a bad deal.

Does Diddy owe any duty to rip up the contracts he signed with these songwriters when they were very young, naïve, vulnerable and anxious to break into the music industry, now that he is one of the richest men in the music industry; and built his label on the backs of these very artists and songwriters like Mase.

Or, alternatively, a contract is a contract: an agreement between two parties, supported by consideration (cash) and in this instant, clearly a contract for services that were paid for by the label.

And, a label would tell Mase, you wrote an album, we gave you cash, and we have a contract to share in the profits associated with the writing of those songs, i.e., the copyrights therein and the publishing income.

Thousands of readers sounded off on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter.

“Give the man his money Puff,” said one reader on Instagram.

“As an investor, what sense does it make for me to give or sell back the artist’s publishing at the artist request to buy it, when my return on investment is so much lucrative,” said Robert Russum, a businessman. “It’s all about business and nothing personal.”

But Jeff Mabry disagreed.

“Sadly, some of our African-American Attorneys played a role in assisting producers to sell these slave type contracts that raped artists of their royalties and wealth,” Mabry said blaming the handlers of many of the music moguls like Diddy.

Many others still begged the question: if Mase is willing to pay millions for his catalogue to get it back, then what is it worth?

Most likely, it is worth $25 million.

That’s right TWENTY FIVE MILLION! And, that’s being conservative.

The answer depends on what we discuss below, i.e., how many songs did Mase write? How many licenses have been issued for these songs? What are the specific rights that Mase turned over, i.e., full publishing or a share and the percentage splits under the contract.

We discuss hypothetically the standards in the industry, but be clear we do not have a copy of the Diddy-Mase publishing or recording contract.

However, I have negotiated hundreds of music industry contracts and we can use similar contracts, industry customs and my experience of nearly 30 years in the industry and having artists signed to Bad Boy over the years.

Mase The Artist vs. Songwriter: Contracts, Splits & Licenses!

First, let’s discuss the contract and the career of Mase the artist and songwriter.

Mase has said repeatedly that like thousands of young artists, he signed a bad contract as a young naïve new person to the music industry.

When Mase first debut, he showed up as an artist on 112,Biggie and Diddy’s own album for such hits as “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down” and “Been Around the World” and the Notorious B.I.G.’s “Mo’ Money, Mo’ Problems”, which reached number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Mase’s first studio album “Harlem World” then debuted at #1, spawning such hit singles such as “Feel So Good”, “Looking at Me” and “What You Want”.

From 1996 to 1999, as a lead or featured artist, Mase had six Billboard Hot 100 Top 10 Singles, and five U.S. Rap No. 1 singles. His 1997 album Harlem World was Grammy nominated and sold more than 4 million albums.

And, he has sold as a lead or sideman artist in upwards of 50 million plus albums.

But, quietly as kept, he was also wisely penning a number of songs as a collaborator. But, he probably didn’t realize how the publishing game really worked in the long run 20 years later.

As a songwriter, Mase contributed on so many big hits like:

1) Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down byDiddy (No Way Outalbum)

2) Mo Money, Mo Problems by The Notorious B.I.G. (Life After Death album)

3)You Should Be Mine by Brian McKnight (Anytime album)

4) Been Around The World by Diddy (No Way Out album)

5) What You Want by Mase (Harlem World album)

6) 24 Hrs To Live By Mase (Harlem World album)

7) Top of the World by Brandy (Never Say Never album)

8) Love Me by 112 (Room 112 album)

9) Take Me There by Blackstreet (Finally album)

10) Call by Harlem World (The Movement album)

11) Get Ready by Mase (Double Up album)

12) Just Wanna Luv U by Jay-Z (The Dynasty: Roc La Familia album)

13) Breathe, Stretch, Shake by Mase (Welcome Back album)

14) Break Your Heart Right Back by Ariana Grande (My Everything album)

15) Loyal By Chris Brown (X album)

These 15 songs are a handful of the dozens of songs that Mase recorded and in many cases received writing credit on as a songwriter.

Collectively, these songs have been licensed hundreds of times and have sold millions of copies. Under a publishing deal with Diddy, the publishing arm of Bad Boy would collect royalties and issue licenses on millions of dollars in songwriting income worldwide.

Mase left Bad Boy Records, and did deals with other labels, but his publishing (or song catalogue for his hits) most likely primarily stayed partially owned by Diddy’s publishing division, as is standard in the industry. And, Diddy’s company would collect on any song written during the term, regardless if the song appears on a Bad Boy album release or any other label, digital or streaming.

So it is clear how the catalogue could clearly be worth well over $25 million dollars, given that most of the songs above all cracked the Top 10 on the charts domestically and internationally in some cases.

And, now Mase is screaming “I want my publishing back” as so many artists have done in the past.

This cry has been an echoing chant for decades since attorney Londell McMillian and Prince claimed the Purple icon had signed a slave contract and Prince wore the emblem on his face.

For years, the music industry has coined the term “standard contract” for the most egregious contracts ever. A contract that calls for an artist to turn over his songwriting royalties and record 5 to 7 albums is considered “standard”.

And, this standard contract often allows the record label to cross-collateralize income from every pot to pay off the other.

So if your album is made for $4 million, the label can tap into your songwriting royalties to pay off the cost of your album before you receive a dime, i.e., cross collateralize.

Toni Braxton exposed it all when she released her album on LaFace record and sold millions of records, but did not see any significant money.

But, most recently the Lox gained a lot of respect when they shared their story and give some insight as to how their careers were allegedly handled when they were at Bad Boy.

In 2005, the urban music industry went primetime on the issue of songwriting and “publishing” and collecting your royalties when the well-known hip-hop group stepped on the mic at Hot 97 in New York and lashed out at Diddy for his control over their publishing.

Many people were very surprised by these allegations and even more shocked that the hip-hop group went public on NY radio. The group also took their protest to the streets by distributing T-shirts to fans that said, “Free the LOX” and “Let the LOX Go,” which did much to impress and sway public opinion in their favor.

Said a frustrated LOX member Styles P, during a radio interview, “Imagine working for years, hard work, and somebody that has nothing to do with your songs that is getting the bulk of it. You’d be totally, utterly frustrated. And, you tryin’ to get around it for years and you call about it with lawyers, but people are too powerful.”

Mase has done the same with his Instagram post some 15 years later with the help of social media and never ever before seen publicly outcry. For the benefit of many to come, he has created a heated conversation about artists rights and the labels who own them.

But, the supporters of these contracts argue, with a straight face, that this is the music business: signing a bad multi-deal contract.

They accept that these contracts take an artist or songwriter 10 plus years to complete and requires you to record 5-7 albums, while sharing in the income associated with any songs you write, i.e., a “Publishing Deal”.

This “Publishing Deal” is signed concurrently with the recording contract; or it is a clause within a bigger contract.

Many labels heads, who refuse to go on record for this article, will tell you privately, “We take the risk as the record label and put up all the money, so it is the way the business works…it’s our standard contract.”

That standard contract has now become an even more inclusive one-sided deal that works against the artist and songwriter like Mase called the “360 Deal”.

And with the advent of the digital explosion, labels make the argument that due to a decrease in CD sales, an artist “must” sign a 360 deal that turns over significant rights to not only their CD sales, but merchandising, publishing, touring and other related income streams for the risk the label is taking.

A 360 deal is just that: a label sharing in the income from the whole 360 circle of income an artist or songwriter could have in his or her career.

Mase is arguing here that he signed a bad contract and did not realize it and is willing to buy the rights back for a 7 figure check. He may not have had a full 360 deal, but clearly signed away his publishing and recording rights at the time (mid 90s) before the digital explosion created the 360 deal.

As a result, the Justin Combs Publishing team or any other entity unknown publishing arm affiliated with Diddy’s Bad Boy Records, issues hundreds of licenses annually from its music catalogue of over 1000 songs, that includes dozens of Mase’s songs under his contracts.

And, it is important to note that of these 1000s of songs, Diddy or his company does not own the entire copyright in many of the songs, but owns a percentage of each song, i.e., a split share as discussed below.

What are the Splits & The Statutory Rate Under the Copyright Act

We may never know what the splits are for Mase’s deal with Bad Boy as a songwriter. However, we know that a typical deal “splits” the publishing up with the various writers and their publishing companies.

In the “standard” agreement, the label would take 50% ownership of the publisher’s share and the writer, like Mase, would keep the writer’s share.

Splits are so critical to understand because they determine what you will get as a writer when the song is released whether on CD, digital, jingles, commercials, etc.

The Copyright Act has a provision that sets forth the full rate of payment if you are a copyright owner in a song.

The full statutory rate, called “full stat” for short, is the ceiling for royalty payments to writers and publishers under the Copyright Act of 1976, as amended. The statutory rate applies to all audio recordings that are made and distributed from the time the new statutory rate goes into effect until the time it is upgraded, regardless of the date of the mechanical license or the date that the particular recording was initially released.

For example, if Mase released a new album in the United States during his contract, and a song on that album was licensed at the full statutory rate, the publisher and writer of the composition, i.e., Mase, would receive a combined 9.1 cents for each album sold as a CD.

Until 1978, the most that a songwriter or publisher could expect to be paid was two cents per song, but that changed significantly since that time period, and Mase is correct that his catalogue of songs is worth millions, given the platinum selling success he has had.

It is important to note also that unless you are one of the industry’s top songwriters or artists (who is also a writer), it is extremely difficult to command the full statutory rate. Record companies are in the business of making money, so a lot of the time labels negotiate with songwriters to reduce the royalty rate that they will receive. This is a particularly common strategy practiced on new songwriters who have not yet established a name for themselves.

This reduced rate is known as the three-quarters rate or “three-quarters stat.” Under three-quarters stat, a writer would receive .06825 (6.8 cents) of a .091 (9.1 cent) statutory rate. Some people in the music industry may tell you that songwriters never receive the full statutory rate and that it is common knowledge that the three-quarters rate is the going rate for songs.

However, it’s important to stress that this contractual detail would be determined on a case-by-case basis and that well-seasoned writers will rarely work for three-quarters rate.

But, for Mase we can use the full statutory rate under the Copyright Act.

Currently, the statutory mechanical royalty rate for physical recordings (such as CDs) and permanent digital downloads is 9.1¢ for recordings of a song 5 minutes or less, and 1.75¢ per minute or fraction thereof for those over 5 minutes. Here is how you calculate the math.

Song up to 5:00 minutes = $.091

Song up to 5:01 to 6:00 minutes = $.105 (6 x $.0175 = $.105)

Song up to 6:01 to 7:00 minutes = $.1225 (7 x $.0175 = $.1225)

Song up to 7:01 to 8:00 minutes = $.14 (8 x $.0175 = $.14)

So, from this chart, we see a payment of 9 cents or 14 cents could be due to Mase on a song going platinum and appearing on a CD.

Thus, if the CD sells platinum, i.e., 1 million copies, Mase could see anywhere from $91,000 to $114,000, depending on what “split” he got on the song and how he split up the publishing on the song.

If he wrote several songs, you could run a multiple of the number of songs. Also, keep in mind, rarely would he see the full 9 cents as most songs on the Bad Boy label have several songwriters, splitting this 9 cents.

For example, let’s look at how this applies for “Mo Money Mo Problems”. The song, according to publishing reports, says there are 6 songwriters: Mase, Christopher Wallace (Biggie), Diddy, Stevie J, Bernard Edwards and Nile Rogers.

For the sake of this hypothetical review, if the song ownership is split up into six equal shares, Mase would own 16.6%.

It doesn’t sound like a lot right?

Wrong!

If the song sold 20 million records, whether on its initial album release, on compilation records, best of records, all time Hip-Hop greats and a litany of other uses, you are looking at a staggering figure.

The 9.1 cents (or 9 pennies) is divided by 6 songwriters; and then multiplied by 20 million.

Thus, Mase’s take home as a co-songwriter would be: $303,333.30 cents for one song.

Now let’s assume Mase co-wrote on about 30 songs and had a similar co-share of 1/6th or 1/5th or whatever on those 30 songs.

You would be looking at a total worth of nearly $10 million dollars for the catalogue in present day value.

Assuming also, Justin Combs Publishing holds the rights for 35 years until he filed a reversion notice and the income could easily triple that number, when you consider re-issued music, TV licensing, commercials, jingles, etc.

The Diddy owned publishing company would reap a great deal of the profits from his publishing and it is why Mase is outraged.

And, keep in mind, I am only talking about CD sales when I use the 9.1 cents per CD sold that features the song. For purposes of this article, I am not talking about the recent deal Spotify and Pandora and other sites did in agreeing to pay an increase in royalties on streaming outlets.

For example, you have Spotify, Apple Music, Google Music, Tidal, Amazon Music and Pandora, among more than a dozen music streaming services.

If Mase’s contract included technology known now or discovered later, like these outlets, the publishing company owned by Diddy would also administer these licenses. And, you are talking millions of streams and millions of dollars.

I took a quick look at YouTube’s Mase songs and saw over 100 million streams. This could be anywhere from $50,000 to $1,500,000 depending on which services we use (some pay $.0003, others pay $0.017, all depends on where the songwriter is streaming and the payout process or rate of the service).

It is also important to note that Diddy is not the first label head to sign an individual as an artist but own all the songs of the artist signed to the label.

Recall that Berry Gordy owned Motown, sold it in the 80s, but kept the multi-million dollar JoBete Publishing that owned all of the great music of the Motown era of the 60s.

Even though many of his original Motown artists had left for CBS or Sony, Gordy still owned the hit songs from their early Motown success. (Gordy would make millions off the catalogue for decades before selling a large stake for approximately $132 million in total to Universal Publishing).

Mase is no different than a Motown artist: freed from Bad Boy as an artist but trying to take part in some of his original hit songs.

Also of similar note, when Michael Jackson died Paul McCartney was still reportedly upset that Jackson purchased a portion of the Beattle Catalogue from Yoko Ono (the widow of John Lennon).

At Jackson’s death his total catalogue, which included Elvis’ was worth 2 Billion dollars. Jackson catalogue is being licensed worldwide yearly.

As is the Mase-Bad Boy catalogue through the Diddy publishing arm.

The licenses, samples, remakes and other uses for several popular songs, will stand to make a songwriter millions of dollars given the multiple platforms the music can be used for in this present day.

Licensing and Sampling of the Mase Songs

When an artist has a hit record, a company owning rights to that song, can send out 100s of licenses per year for covers or samples taken from that one song.

For years, you will see our law firm name mentioned on dozens of albums as the publishing administrator for songwriters on various gospel, hip-hop and R&B albums.

Most recently, Jay Z released his Family Feud song and as widely reported in the press, we worked closely with his team to grant him the licensed use of the legendary Twinkie Clark song “Ha-Ya (Eternal Life)” as the hook to this multi-platinum song. Throughout the song you can hear Beyoncé singing in the background “Higher, higher, higher, higher” and Clark, a member of the famous Clark Sisters, wrote the classic bed of the song that Jay-Z flows over.

Clark wrote the song in 1980 and like many songs in her catalogue, the song has been licensed dozens of times and for a songwriter that is significant revenue.

And, it is that type of revenue that Mase is fighting for: the ownership and right to license his own music, complete and clear from sharing with Diddy.

It is important to note that a license is needed whether someone does a cover of a song; or just takes a sample from another song and uses it in a new song.

A cover is when a singer or performer sings the exact same song and does a literal “cover” of that same version without changing pretty much anything.

A sample is where you fuse a snippet of someone’s song into your new songs.

For example, Biggie used Herb Alpert’s base line from the hit song “Rise” in his diamond plus selling “Hypnotized”. Most people never heard of Herb Alpert (former owner of A&M records) and a major industry player.

Thus, for Mase, the license, sample or re-use of his songs is worth millions of dollars when used in by Diddy and others.

Also keep in mind that the publishing income goes beyond just the CD sales.

Mase’s music is used in commercials, movies, jingles, sheet music and on digital streaming with Spotify, Pandora, Google Music, Amazon, YouTube and others.

He would also earn publishing income from ringtones, remixes, jingles, downloads, videos, digital gaming, soundtracks, and tons of other uses for a given hit song.

One look at the above-listed chart topping 15 songs written by Mase, among others, and it’s easy to understand why he is bitter now about his contract.

But, again, there is no duty or law that requires Diddy or Puff, as some still know him as, to rip up the contract with Mase for $2 million or any millions for that part.

Real Talk!!!

As Biggie said, it is all about the Benjamins—getting and keeping them!!!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: James L. Walker, Jr., is the Author of This Business of Urban Music (Random House), an entertainment and business lawyer and law professor of over 25 years. He is based in Atlanta, GA and can be found at www.walkerandassoc.com or email if you have questions about this article: [email protected] (@jameslwalkeresq).

More Stories

Congressman Maxwell Frost Statement on the Passing of Florida State Senator Geraldine Thompson

Cheap Safari Tours in Tanzania – Get the Best Deals with Visit Tanzania 4 Less

Introducing the Kids Free Trip to Africa Class of 2023!