⇨

Sign In

Join

Donate

Law

History

Before the Movement: The Hidden History of Black Civil Rights by Dylan C. Penningroth. Liveright, 2023. 496 pages.

AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS frequently depict the Civil Rights Movement as a heroic tale about the courageous rise of a social movement led by charismatic African American individuals and dedicated organizations that turned to the law as a shield against the long-standing discrimination and subordination perpetuated by white supremacy. Implicit in this standard account is the sense that the law came late to the historic “freedom struggle” for racial equality. According to the conventional narrative, until the 1954 landmark Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education, the law was primarily a tool of racial domination, especially in the South. As a result, Black Americans feared the law and sought to avoid a justice system that provided them with little justice of any kind.

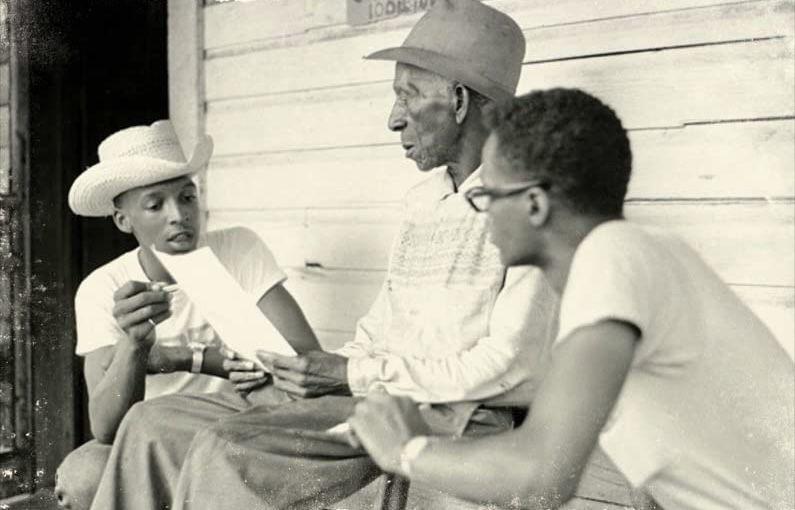

In his brilliant and provocative 2023 book, recently released in paperback, UC Berkeley legal historian Dylan C. Penningroth challenges nearly every aspect of our traditional understanding of civil rights history. His compelling narrative paints a fuller picture of what he refers to as “Black legal lives.” Through prodigious research in archival materials, including obscure local and county court records, Penningroth chronicles “how ordinary Black people used law in their everyday lives.” He shows how they relied on the law to make contracts; acquire and transfer property; manage family relations such as marriage, divorce, and inheritances; and govern nonprofit corporations like churches.

Thus, well before the mid-20th century, African Americans were robust legal actors. Through practice and experience, they developed what one Black farmer called a “goat sense” about the law—a commonsense understanding that God gave a billy goat. This goat sense was particularly astute when it came to property relations and contractual arrangements—two of the fundamental legal pillars of modern American capitalism. Black Southern tenant farmers, for example, understood—even during the height of Jim Crow—that a renter at the end of a lease had the right to take back “anything that aint tied down”—a right long supported by the common law and memorialized in contemporary legal treatises. Even during slavery, Penningroth shows, there was a tacit understanding that enslaved people could make binding bargains such as loans with each other and, on occasion, even with whites. These property and contract rights, of course, were not recognized formally by the “law on the books.” But they often had a strong hold with the “law in action” in the form of local customs, community norms, and regional legal cultures.

In highlighting the commonplace rights of property and contract, Penningroth broadens our vision of the historical meaning of civil rights. “For African Americans, property and contract were civil rights,” he writes. “African Americans hammered out their relationships with one another and with white people within the law, not just in struggle against it. And in doing so, they helped make and remake the law.” For too long now, Penningroth contends, we have forgotten just how regularly Black Americans made use of the law, legal institutions, and legal processes to live their daily lives.

By uncovering this “hidden history,” Before the Movement addresses an apparent paradox about the standard legal history of the Civil Rights Movement: how did a group historically subjugated by the legal system come to rely on it as a vehicle for full citizenship and social change? Part of the answer rests with the long history of Black legal lives. Penningroth argues that African Americans did not come to the law in the early or mid-20th century as naive supplicants seeking refuge in its protections. Law did not just fall out of the sky for them. Rather, throughout much of the 19th century and well into the 20th, Black people were active legal agents familiar with a vernacular sense of individual rights and jurisprudential principles. They exercised those rights and adhered to those principles in the shadow of cautious courts, which, for the most part, upheld the rule of law. Thus, when the mid-20th-century freedom struggle turned to law, African Americans were familiar with its untapped potential.

Penningroth is clear to state that his evidence does not suggest that Black Americans in the earlier periods were able to overturn white supremacy in the South. The law remained, for the most part, a hostile, fearsome, and sometimes lethal power. A legal system dominated by racism often refused to recognize not only Black people’s civil rights but also their basic human dignity and full citizenship.

But there was much more to the law. By focusing on how Black Americans used the legal system in their everyday interactions, mainly with each other, Before the Movement recovers a lost past—one that helps us see how legal relations were integral to Black daily life. In this sense, Penningroth’s recovery of this forgotten history is a major contribution not only to US legal history but also to our broader understanding of African American and US social history. Before the Movement essentially recenters the history of race relations away from a myopic focus on Black/white entanglements and toward a more panoramic vision of the everyday interactions of Black commercial and social life.

For too long, Penningroth argues, Black history was “almost synonymous with the history of race relations, as if Black lives only matter when white people are somehow in the picture.” His book masterfully succeeds in demonstrating just how much the law mattered to Black Americans’ daily lives. In his retelling, “Black people—not race relations—are the center of gravity.”

Penningroth is able to recover this forgotten history because of his innovative and labor-intensive research. When he first began working on this book, Penningroth learned that the most revealing historical documents were not stored in traditional archives. Instead, he had to venture into the dusty back rooms and musty basements of county courthouses to recover just how the law operated for ordinary African Americans. He worked with a team of research assistants, with funding support from the American Bar Foundation, where Penningroth is an affiliated research professor, to create a massive and impressive database of local court cases.

The key to his data collection project was to identify the race of litigants—a fact regularly elided by formal court records. His research team analyzed over 14,000 civil cases from two dozen courthouses in five states and the District of Columbia. From this initial pool, they used census data to match and analyze more than 1,500 cases that involved Black litigants. This remarkable database and other archival sources comprise the book’s core evidentiary foundation. Using this data, Penningroth shows that the vast majority of lawsuits (98 percent of his cases) were legal disputes between Black litigants. In his period of focus, which stretches from the 1830s to the 1970s, Black Americans were actively using the legal system to manage their daily lives, from marriage contracts to the conveyance of property to the operation of their nonprofit civic associations.

Given that much of the legal interaction that Penningroth uncovers took place between Black people themselves, Southern white officials had little interest in disrupting the fundamental rhythms of daily life. “[W]hen white people did recognize Black people’s property or contracts, it was not out of a sense of fairness or paternalist obligation, or because formal legal rules occasionally trumped white racism,” Penningroth writes. “White people recognized Black rights because life’s ordinary business could not go on if whites could not make contracts and convey property to Black people.” Sheer practicality undergirded the rule of law.

The deference to routine workability was, of course, rooted in the interests of whites. Noted legal scholar and critical race theorist Derrick Bell observed long ago that “the interests of blacks in achieving racial equality will be accommodated only when it converges with the interests of whites.” With an implicit nod to Bell’s “interest-convergence” thesis, Penningroth shows just how such legal accommodation operated on the ground in many Southern states and localities.

In addition to broadening the conventional notion of civil rights, Before the Movement also skillfully documents how Black Southerners relied on the “law of associations” to govern their many civic organizations. In what is perhaps the book’s most arresting chapter, Penningroth analyzes how the creation, operation, and dissolution of nonprofit corporations such as Black fraternal orders, schools, and churches were deeply rooted in the law. Scholars, to be sure, have long noted the importance of religion and the role that Black churches and mosques played in the “freedom struggle.” But once again, Penningroth complicates any simple understanding of the role of religious organizations in Black lives. Rather than romanticize Black churches as harmonious organizations involved in “uplifting the race,” Penningroth shows the real-world discord and tension that existed within Black churches, just as in any other civic institution, and how parishioners and leaders frequently sought to resolve these tensions through the law.

By examining the corporate charters and bylaws that helped establish these “voluntary associations,” Penningroth demonstrates the legal power dynamics and gender imbalance that underpinned many congregations. Under most church bylaws, ministers and trustees, who were mainly men, had the legal right, and hence the power, to run the churches. Meanwhile, women—who frequently made up the majority of the rank-and-file members and donors of many churches—had only limited legal privileges as mere members of the corporation. This asymmetry in power, supported by the authority of private corporate law, often led to conflicts about church management. At times, members could reign in autocratic pastors through a church’s constitutionalism or by suing leaders in a secular court. On other occasions, when those legal measures failed, some church members turned to extralegal efforts, including physically removing pastors from the pulpit.

In the process of attending to the interlocking power of property, contract, and corporate law, Penningroth focuses mainly on nonprofit corporations. Of course, he acknowledges the significance of Black business associations like the Baptist Publishing House, which ran a multimillion dollar corporation and had a large physical footprint in Downtown Nashville. But one wonders if Penningroth could have done more to show, as some recent business and economic historians have, how Black businesses and other commercial enterprises were a fundamental part of modern American commercial life. Doing so would have allowed him to use his remarkable research to contribute to the growing interest in “racial capitalism.”

To be fair, Penningroth is not an economic or business historian; he is a social and legal historian. Indeed, he is one of the country’s leading figures in this area. With Before the Movement, Penningroth has provided a beautifully written narrative—one that braids his own family history with a deep analytical account of the legal past, and in the process corrects the standard textbook version of civil rights. He shows us that law is made not only in legislatures and courts but also in our everyday interactions, and that, even when African Americans were excluded from the formal lawmaking process, they were forceful legal actors, vigorously using civil rights and privileges in their daily lives.

LARB Contributor

Ajay K. Mehrotra is a professor of law and history at Northwestern University and a research professor at the American Bar Foundation.

Share

The 1964 Civil Rights Act was a triumph of one vision — one history — of one America over another.

Jeneé Darden interviews Jeanne Theoharis about her most recent book, "A More Beautiful and Terrible History ."

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

Donate

During the five-week intensive online workshop from June 23-July 25, 2025, connect with visionary publishing professionals, cultivate a diverse network, and get hands-on book and magazine experience.

Apply by April 1

Subscribe

Los Angeles Review of Books

The Granada Buildings

672 S. La Fayette Park Place, Suite 30

Los Angeles, CA 90057

The Los Angeles Review of Books is a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting and disseminating rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts.

Masthead

Supporters

Volunteer

Newsletter

News & Press

Shop

Contact

Privacy Policy

General Inquiries

[email protected]

Membership Inquiries

[email protected]

Editorial Inquiries

[email protected]

Press Inquiries

[email protected]

Advertising Inquiries

[email protected]

Purchasing Inquiries

[email protected]

Recovering the Forgotten Past of Black Legal Lives – Los Angeles Review of Books

More Stories

Oakland mayor’s chief of staff fired after referring to black people as ‘tokens’ in resurfaced note: reports – New York Post

Jasmine Crockett Called Out For ‘Cotton-Picking’ Comment – Black Enterprise

Lefty Texas Rep. Jasmine Crockett suggests US needs migrants because black people ‘are done picking cotton’ – New York Post